What if you wake up one day and find out that you were not any human but a mere butterfly, who instead of fluttering around with glee dozed off into a deep sleep and dreamt about being a human? The shock and sorrow you feel would be immeasurable. You might even go to a nectary and drown your sorrows in a desperate attempt to make yourself happy.

I did go overboard, but there are such times in physics too. Funny times, when people reach the pinnacle of understanding of the universe, declare that everything is now understood, only to get laughed at by the universe, who still has many tricks under its sleeve, and get pushed down a deep pothole of despair they can never recover from. Well, in the 1980s, it was the turn of the proton to pull the carpet from under the physicists’ feet, causing them to roll downhill in the understanding of the exact mechanism of the grand construct called the universe.

The Proton…

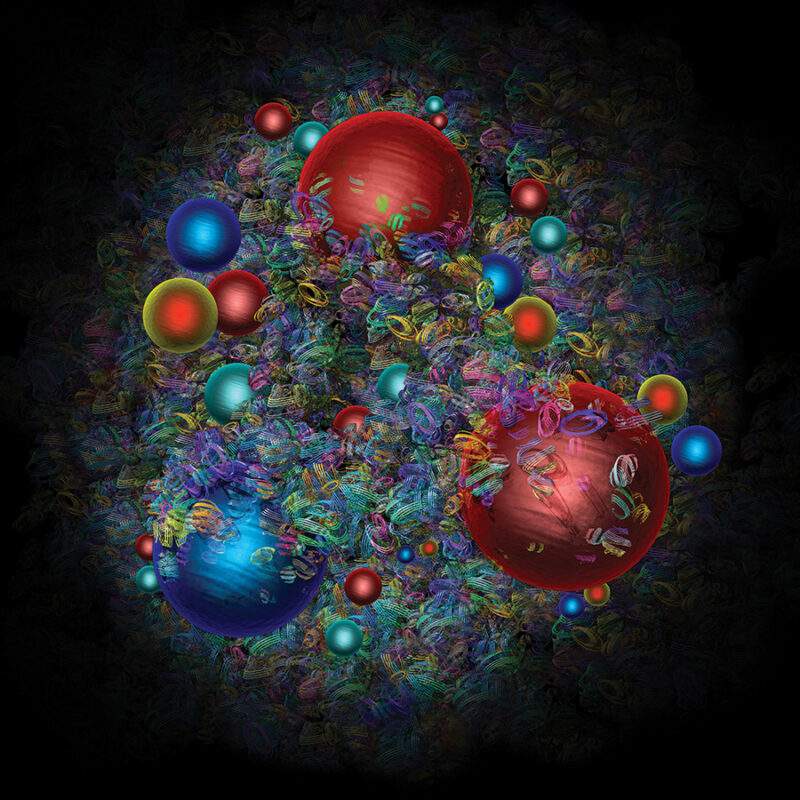

Democritus of the 4th century BCE lived a peaceful life, and so did everyone before Rutherford of the 20th century AD. Rutherford gave his nuclear model of the atom, dividing the indivisible ‘atomos’ into a positive nucleus and negative electrons. The protons, along with neutrons, form the positive nucleus of the atom. For several years these protons were believed to be elementary, i.e. indivisible. The proton, just like other particles, had a mass, charge (+e) and also a spin ½.

[Image: ShowMe]

Enter Gell-Mann, the indivisible protons were no more indivisible but were now made of weirder particles called quarks.

Quarks are weird. They carry a fractional electric charge (Millikan, if he were alive then, would have screamed in horror, since he had shown that electric charge is always integral), a half-integral spin and are so fond of each other that it is physically impossible to isolate a quark (the property is called quark confinement).

[Image:IFIC]

The quark model of the proton states that the proton is made of three quarks, two of the type u and one of type d. The u type has a charge of ⅔ e and d has charge -⅓ e, resulting in a net charge of ⅔+⅔-⅓ = 1 of the proton. These quarks interact with each other through the strong nuclear force, by exchanging particles called gluons.

Quark confinement meant that it would never be possible to detect a single quark. It would always be a system of two or more quarks that can be detected. So for some time, the theory of quarks was never an established theory but was only a mere mathematical construct.

In further years, indirect methods to study the internal structure of the nucleons were devised. Methods like deep inelastic scattering have provided sufficient evidence to show that the charge of the proton is not uniformly distributed, but is concentrated at three points, as expected from the quark model. This established the fact that the proton is made of three point-like quarks.

[Image: Wikipedia]

The Proton Spin Crisis…

Let me present some facts here.

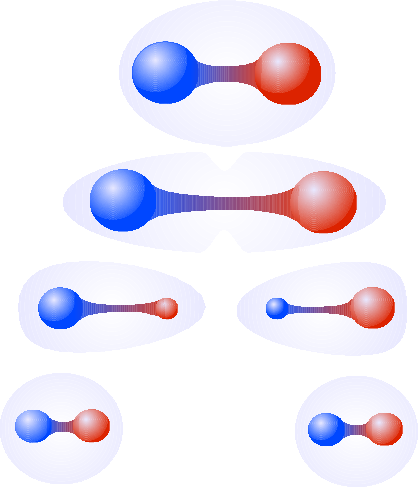

There is the proton with a spin ½.

Then there are quarks with spin ½.

How can we get to the spin of the proton from the spin of the constituent quarks?

In principle, this is straightforward. Take two quarks with spin +½ and one with spin -½. Since spin adds algebraically, you would be left with spin ½+½-½ = ½, which is the spin of the proton. To speak generally, take two quarks with spin pointing in one direction and one pointing in the opposite direction, you should end up with the spin of the proton. Easy right?

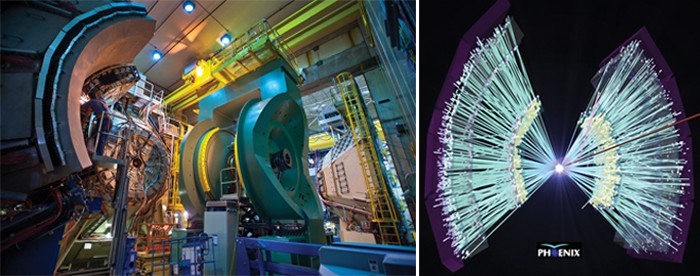

In 1988, the Europen Muon Collaboration at CERN ran collision experiments to detect the spins of the constituent quarks of the proton. When they published their results, the entire physics community gasped a breath of shock as the results implied that the spin of the proton was not from the quarks as it was expected. In fact, the calculations showed that the contribution of the quarks’ spin to the proton’s spin could never be more than 24%, i.e. it was not even a quarter of the proton’s spin.

What’s worse, the results showed that contribution could be even as low as 4%, which is practically zero. It was a result that left the world in a state of shock. How could the theory of quantum chromodynamics, which had worked perfectly everywhere else, give a wrong result? This puzzle was termed the proton spin crisis.

Attempts of resolution…

If it wasn’t from the quarks, then where did the spin come from? This question baffled physicists worldwide. Some even went to the extremes, suggesting abandoning QCD. But some others looked for resolutions in other places.

The uncertainty principle states that the more precise you know the position of a particle, the fuzzier the momentum becomes. Since the quarks are confined inside the tiny proton, they should have a huge uncertainty in momentum. So they should be moving randomly here and there inside which should give rise to a kind of rotation, contributing to the proton spin. But this orbital term was difficult to observe, so people looked at another candidate – the gluons.

Measuring the spin contribution of the gluons takes a lot of precision and hence it took about two decades for the data to start surging in. But to the disappointment of everyone, the gluon contribution was not enough to account for the spin of the proton.

[Image: Physicsworld]

Another possibility would be that of the sea quarks. The inside of the proton is a hub of gluons, and where there are gluons there happens the quark-antiquark pair production. The pairs produced in this manner contribute to a sea of quarks and antiquarks inside the protons and are hence termed sea quarks. And one suggestion is that the missing spin will be accounted for by the sea quarks. But there is no concrete proof yet to confirm this suggestion.

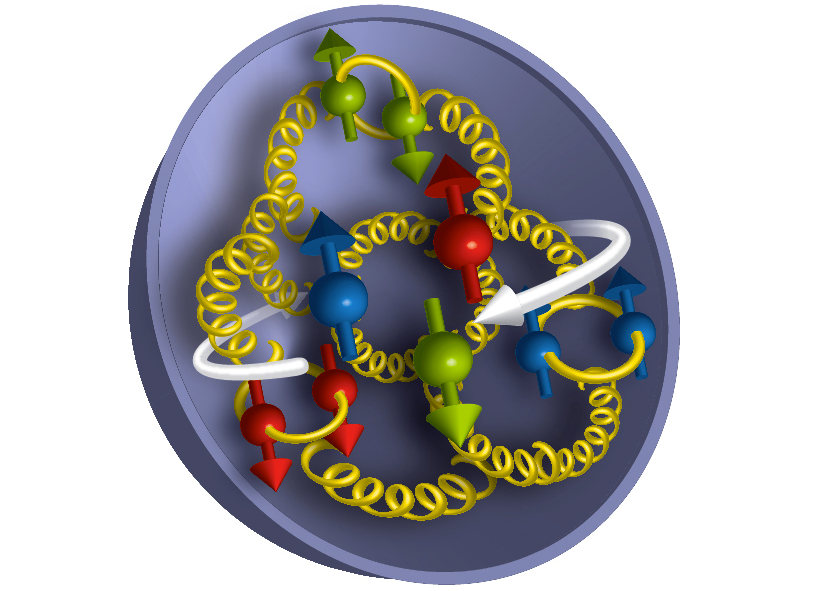

Current Explanation…

Currently, it is thought that the missing spin is accounted for by all the above possibilities – the quark angular momentum, gluon spin and angular momentum and also the sea quarks. But there is no proper resolution of the crisis yet, and people worldwide are still working on the puzzle. The issue with the problem is that QCD is extravagantly difficult to work with. Tackling infinities here and there, analytical solutions to QCD equations is next to impossible. Only numerical approximations like the lattice QCD solutions etc are the available options.

Part of the difficulty arises from the fact that the strong nuclear force, as the name suggests, is a very strong force compared to the other forces of nature. Another factor leading to this difficulty is the fact that gluons interact with each other, unlike the photons which do not interact with other photons, giving rise to really ugly terms in the equations.

[Image: Medium]

Physics is ingrained with puzzles and crises every here and there, each one of them reminding us of the insignificant role we play in the universe – a role of a mere spectator who can only look at the grandiose of the universe with eyes wide open.